I love this guy so much.

He brings me joy.

I love this guy so much.

He brings me joy.

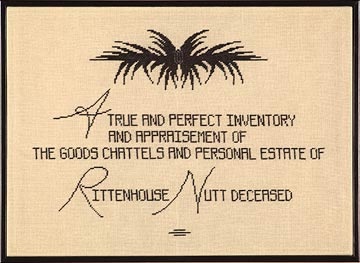

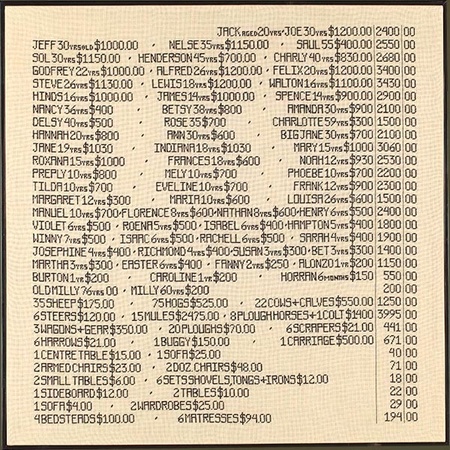

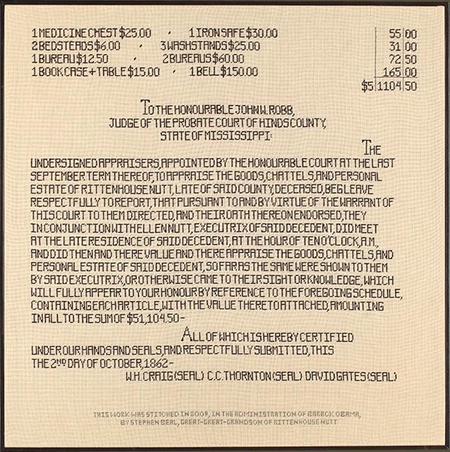

Fiber artist Stephen Beal’s embroidered inventory and appraisal of the estate of a slave owner — someone who happened to be a very distant relative of his. The artist was given the actual document a few years ago and conceived this stark, stunning piece.

Read down the document. See how “goods” are lumped together. And wait until you get to “Old Milly.”

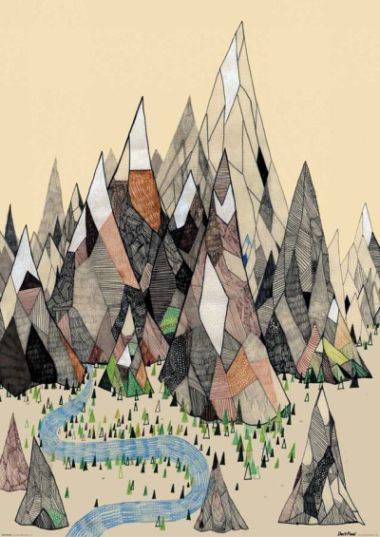

By artist Sam Ashton, using “woodblock” drawing.

I love this. I’d like to own it. Gorgeous.

Yep. I can now say I have cried at a piece of jewelry not given to me by a loved one. Or even mine, boo hoo.

One of my favorite mixed media artists, Deryn Mentock — she does primarily jewelry — has created an absolutely gorgeous necklace, inspired by the biblical story of Mary, sister of Martha, breaking open an alabaster jar of perfume and anointing Jesus’ feet with it. I love the way she describes the significance of the biblical story and the various elements she used to create the piece. You could just feel how she poured her whole heart into that piece. What can I say? It just got me. Looking at her stunning piece, I felt like I could literally see that story unfolding and I just teared up. I did.

So go check out this necklace — and her whole site, actually. Wonderful work, lovely spirit. I know I’m gushing like a giddy schoolgirl or potential stalker or something, but …. never mind all that! Go see. It’s beautiful. Someone needs to snatch that piece up.

This is the post I referenced below, the one that was supposed to be finished yesterday. Nevertheless, it’s here now.

One of the most emailed questions I get about this blog is “Who is the artist featured in your banner and side bar?” You know, I’ve had this new blog for over, uhm, two years now, but I’ve never written about the man who is basically the star of it.

Shame on me. Really.

Today (uh, yesterday) seems (seemed) like the perfect day to finally remedy this appalling situation, because today, (again, that would be yesterday) in 1825, the artist himself was born. One of my favorites, obviously.

So Happy (now-belated) Birthday, William Bouguereau!

(Here’s my girl, my beloved banner girl, Petite Maraudeuse/Little Thief. Now you can see her in her entirety and see the context for that look in her eye. She’s an angelic little scofflaw. I love her. I love all my Bouguereau girls.)

William Bouguereau, a French artist schooled in the classical, Academic style, was hugely successful for most of his lifetime, lauded within the classical community and by rich patrons of the arts. His themes were alternately religious and pagan; fantastical and earthy. He loved painting nymphs and goddesses and bathers and children, creating a light-infused dreamworld so soft and clear and precise that it seemed it must surely be real.

Fred Ross, Chairman of The Art Renewal Center, says of Bouguereau:

Bouguereau ….. was especially sensitive to the difficulties in growing up. In his depictions of childhood, he manages to capture the most exquisite subtle nuances of insecurity, self-consciousness, the search for identity, the struggle with budding sensuality and the conflict between the need to mature and the joy of wanting to stay immersed in childhood.

With an imagery at once extraordinary, fanciful, and sublime, he often conjured an ethereal universe of transcendent beauty – an idyllic and shimmering realm from which ugliness, poverty and pessimism were forever banned. These works he balanced by those reminding the more fortunate in society to care for the young, the poor and the suffering.

But even as Bouguereau’s career and reputation burgeoned, as he became a celebrity, basically, art philosophies began colliding. Impressionism was gaining popularity. Degas, Monet, Renoir, and others exploded onto the scene. The art world of 19th century France was becoming polarized: Academic vs avant-garde; classical vs Impressionism. He was soundly criticized by the up-and-comers for, basically, not getting with the program. He was “artificial” or just a “technician” or not “progressive.” Degas and other artists mocked his style, but Bouguereau just did what he did. He wasn’t swayed by all the newness swirling around him. The storm of rebellion against traditional values in painting raged around him but he just continued painting his dream world of virgins and myths and childhood — his own idea of beauty. As much as I love the work of the Impressionists, I have to applaud Bouguereau for this, for sticking to his own principles, for not allowing himself to be swept away in the churning tide of change. I mean, why should he? Why surrender everything he’d learned, everything he was, everything he’d become, to what a select group of, well, somewhat rabid artists and elites thought he should be or should become? Good for you, Bouguereau. That’s part of why I love you. He was true to everything that made him him. He wasn’t Monet or Degas or Pissarro and he wasn’t going to try to be. Whatever artistic furor blew outside his window, Bouguereau basically could not give one tiny rat’s bottom, although he probably wouldn’t have said it that way. (Because, obviously, he would have said I do not give one tiny rat’s bottom in French.) Still, his resolute self-awareness and perseverance make me want to stand up and cheer. He knew what he was and what he was not.

As if attacks on his work weren’t enough, his critics slandered him personally and relentlessly. He’s stingy, they’d say, despite the fact that he frequently organized sales to benefit his struggling colleagues. He’s a lecher, they’d say, despite no concrete evidence whatsoever. He only wants to paints nudes, they’d say, despite the fact that nudes comprised only about ten percent of Bouguereau’s body of work. (Even so, it is shocking. I mean, we all know that NO artist before him had EVER painted nudes.)

L’etoile Perdue/The Lost Pleiad (Gorgeous. I must be a lech.)

Bouguereau, though, didn’t waste time defending himself or giving any attention to the lies, the rumors, the insanity of it all. He just quietly did what he did. Part of me wants to scream, “Defend yourself, man! They’re all LIES!” but how much creative energy, better spent on his work, would he have frittered away on that? Instead, he took the higher ground. Kept at his work. Let the work speak for itself and for him. You know, it’s mind-boggling to me, the sheer almost tyrannical force that flew at him from certain factions simply because he wasn’t seen as “progressive.”

Here’s what Damion Bartoli, a biographer of Bouguereau’s, says of the effect of the growing Impressionist influence on Bouguereau and other Academic painters of the time:

Little by little, despite their popularity with the public, the most celebrated painters of the Academy – Bouguereau, Gérôme, Cabanel, Meissonier, Bonnat, Lefèbvre – found themselves blacklisted by a group of youthful artists supported by a cooperative press and the fabulous inherited wealth of a few “high priest†patrons of this avant garde who were on the brink of monopolizing the official posts — in the Beaux-Arts, in the teaching profession, and in the curatorial positions of the major museums.

Still, Bouguereau was undaunted. The new fashion simply didn’t suit him. His dedication to his own vision could not be altered or swayed. A master colorist and draftsman, he pursued the perfection of his dream world his entire working life.

Bartoli says of Bouguereau’s habits:

Rising at six o’clock, he would install himself in his studio and stay there without budging until nightfall, appeasing his midday hunger with eggs and his thirst with a glass of water. He received guests, he smoked, he chatted, he joked; but he did not stop – he never stopped. As soon as the light became insufficient for painting, he worked at his voluminous correspondence, then finally; letting his imagination wander, he would search for new subjects, designing new compositions by lamplight, stopping only when weariness got the best of him.

Bouguereau was also a generous teacher. Another reason I love him. He was passionate about sharing his knowledge, championing the work of the Old Masters — Raphael was a favorite — to his students his entire life, while at the same time allowing his students free expression of their own vision and individuality. He taught as he had been taught: technique and freedom. The one was born from the other. I love that mindset — a perfect combination in a teacher, if you ask me. He extolled the virtues of studying the craft of painting and practiced what he preached. In addition, Bouguereau was a trailblazer, advocating for the integration of women into the ateliers and academies. He personally taught women in his own atelier and, later, largely through Bouguereau’s own influence and example, women were allowed into the prestigious Julian Academy and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Late in life, after many years of being a widower, Bouguereau married one of his students, American Elizabeth Jane Gardner, who became an accomplished artist in her own right.

Some students, though, were far less amenable, shall we say. Truly difficult, according to Ross:

The most famous of these was Matisse, who quickly dropped out of Bouguereau’s studio. From the start, the master tried to encourage Matisse, but soon threw up his hands in exasperation, noting the young man’s weaknesses, “You badly need to learn perspective,†he said to him, “But first, you need to know how to hold a pencil. You will never know how to draw.â€

(Clearly, Matisse found his way somehow. But hahahaha. Bouguereau obviously thought he was a slackass.)

His personal life was filled with tragedy. By the end of his life, Bouguereau had outlived his first wife and four of his five children. How he kept creating under the weight of so much sorrow, how he didn’t just shut down, become paralyzed with too much grief, I cannot even fathom, although perhaps a clue can be found in his own quote:

Each day I go to my studio full of joy; in the evening when obliged to stop because of darkness I can scarcely wait for the next morning to come…if I cannot give myself to my dear painting I am miserable.

I love that. He was his art.

Bouguereau died in 1905, his reputation obscured — along with those of other Academic artists — under a cloud of lingering hostility. Impressionism had basically reinvented art; it represented progress, a fresh newborn approach. A traditional artist like Bouguereau, however, had become — even posthumously — a blaring example of “what not to do”; his work was “old establishment,” a rigid dying aesthetic. This was the general opinion towards most of the great artists of the Academie, but Bouguereau seemed to get an extra bite of venom from his detractors. A prolonged catty backlash. I mean, pick up any art history book published from 1910 to 1980 and Bouguereau, if mentioned at all, will be presented as a bad example or perhaps as Matisse’s (really frustrated) teacher. The man who in his day was considered the most important French artist of the 19th century and one of the greatest painters of the human form was basically expunged from art history for nearly two generations. (A similar thing happened to Rembrandt, but that’s another story.)

Now, this is just my opinion, but I think that extra venom has to do with his being a teacher. He didn’t just practice the “old ways,” he preached them to others. Perpetuated them. He was basically a conservator of the methods of the Old Masters he so dearly loved. But practicing the traditional methods in his own work might have been one thing; evangelizing about them quite another. Perhaps mentoring another generation in those “old establishment” ways embittered his critics even more. You’re rigid, Bouguereau, but keep it to yourself. Don’t spread your disease. Of course, this whole thing is just a theory of mine, but it might explain some of the extra measure of rancor Bouguereau has received over the years. What he did, he taught others to do, and perhaps that carried with it a more severe punishment from those who considered themselves more modern and forward-thinking. Again, a theory.

As the 20th century marched on, Bouguereau’s works were lost to basements and attics and dusty storage rooms. People lucky enough to possess one of his gorgeous ethereal paintings didn’t even know what they had. Before the 1960s, it wasn’t uncommon for his pieces to sell for as little as $500. That’s how invisible, how forgotten, he’d become. Uhm, Bouguereau who?? By 1980, though, Bouguereau was experiencing some artistic redemption. The art world was finally giving him a long-deserved second look and his pieces began selling for millions at auction. That being said, he still remains a polarizing figure in art circles, criticized variously for being “unemotional” and “too emotional.” “Full of flaws” and “too perfect.” “An individualist” and “a pushover.” “Weird” and “conventional.” Good Lord. Make up your minds, people. What’s next? “Too tall” and “Too short”? (He was short, actually.) The pendulum swings wildly to this day with Bouguereau. Depending on your view, he’s either the defender of Western civilization or the enemy of progress. Good guy or bad guy. Hero or devil.

I myself can’t quite understand it, really, or it exhausts me or something, because I like to consider the work. I just want to fall into the work of an artist. Relish it. Soak it up. I don’t feel the need to label him a cultural touchstone or a cultural killjoy. Maybe I’m simplistic, simple-minded, whatever. I just love his work and his dedication to it. That’s what gets my blood going. But for whatever reason, for many many other people, Bouguereau stands at the intersection of the age-old debate between tradition and progress. The debate about him is always about more than the merits of his work. (And there have been debates, actual debates, about this man. Getty Museum 2006.) So I understand that all these complications have always swirled around him, I do, I just prefer not to immerse myself in them when I’m looking at his work. Actually, now that I think of it, he preferred that, too. It was about the work, always the work. I’m just gratified to see that after being forsaken for decades, locked in the basement of public opinion, Bouguereau is slowly — for a growing circle of people — being restored to what I believe he was all along: a genius of light and tone and clarity, a master of ethereal fancies and sun-drenched dreams, a man who never strayed from his personal journey toward absolute beauty, the world outside be damned.

So thank you, William Bouguereau. You give me joy.

La Brise du Printemps/Spring Breeze

Please go here to enter The Art Renewal Center’s extensive and stunning Bouguereau gallery. I have that whole site bookmarked. So many gorgeous galleries featuring other Masters of classical realism. On the main page, click on “Museum” and enter your search. Again, this site is devoted to classical realism. You won’t find Picasso, but you’ll find enough beauty to keep you occupied and drooling for hours.

Sheila has a post up with a vast gorgeous array of images of Ophelia through the ages. Etchings, drawings, paintings, photographs of actresses who’ve played Ophelia. It’s a smorgasbord of beauty.

Her post made me remember a piece from one of my all-time favorite artists, Alphonse Mucha, so I thought I’d make my minor contribution to the idea here. It’s one of his Sarah Bernhardt paintings/posters for which he become famous: Sarah Bernhardt as Hamlet, actually, and even though Hamlet dominates the frame here, if you look closely, underneath Hamlet, you’ll see Mucha included an image of Ophelia, in the chill of death, clutching her flowers.

I love contemplating what Mucha intended with the composition — Ophelia boxed in a kind of pretty casket at the bottom, Hamlet’s dark foot breaking the frame — doing what? acknowledging her? reaching to her? oppressing her? what? To me, it’s not accidental that the foot is outside the frame. She is literally under his foot here. It’s not like I picture Mucha having composition issues and being forced to paint the foot out of frame or not giving his subject’s legs and whatnot, like some people I know. Maybe it’s only interesting to me. A roomful of people could go round and round discussing the relationship between these two and, at the end of it, come to a roomful of different conclusions about it. And the views on their relationship shift with the times and the culture. This is a lithograph from 1899, late Victorian era, to give it a context, and based on the feel of the piece, I thought it would be interesting to include a couple of contradictory quotes on the Hamlet/Ophelia relationship from two prominent Victorian women.

The first, from writer Anna Brownell Jameson fromShakespeare’s Heroines: Characteristics of Women:

I have even heard it denied that Hamlet did love Ophelia. The author of the finest remarks I have yet seen on the play and the character of Hamlet, leans to this opinion… I do think, with submission, that the love of Hamlet for Ophelia is deep, is real, and is precisely the kind of love which such a man as Hamlet would feel for such a woman as Ophelia.

~ Anna Brownell Murphy Jameson, Shakespeare’s Heroines:Characteristics of Women.

The second, from a well-known Victorian actress who played Ophelia, Helena Faucit:

I cannot, therefore, think that Hamlet comes out well in his relations with Ophelia. I do not forget what he says at her grave: But I weigh his actions against his words, and find them here of little worth. The very language of his letter to Ophelia, which Polonius reads to the king and queen, has not the true ring in it. It comes from the head, and not from the heart – it is a string of euphemisms, which almost justifies Laertes’ warning to his sister, that the “trifling of Hamlet’s favour” is but “the perfume and suppliance of a minute.” Hamlet loves, I have always felt, only in a dreamy, imaginative way, with a love as deep, perhaps, as can be known by a nature fuller of thought and contemplation than of sympathy and passion.

~ Helena Faucit, Lady Martin, On Some of Shakespeare’s Female Characters (1888).

I, for one, although I like how Brownell states her point, tend a bit towards Faucit’s interpretation. The composition and the general feel of Mucha’s piece makes me wonder if he did, too. Maybe I’m reading too much into it, but, let’s face it, my entire life is based on reading too much into everything.

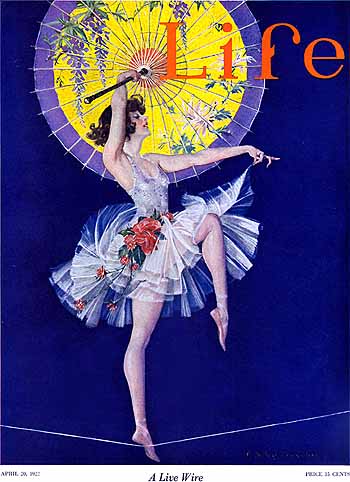

By F.X. Leyendecker, who I just mentioned below:

Look at the colors. So rich. So alive. I just want to dive in and splash around.